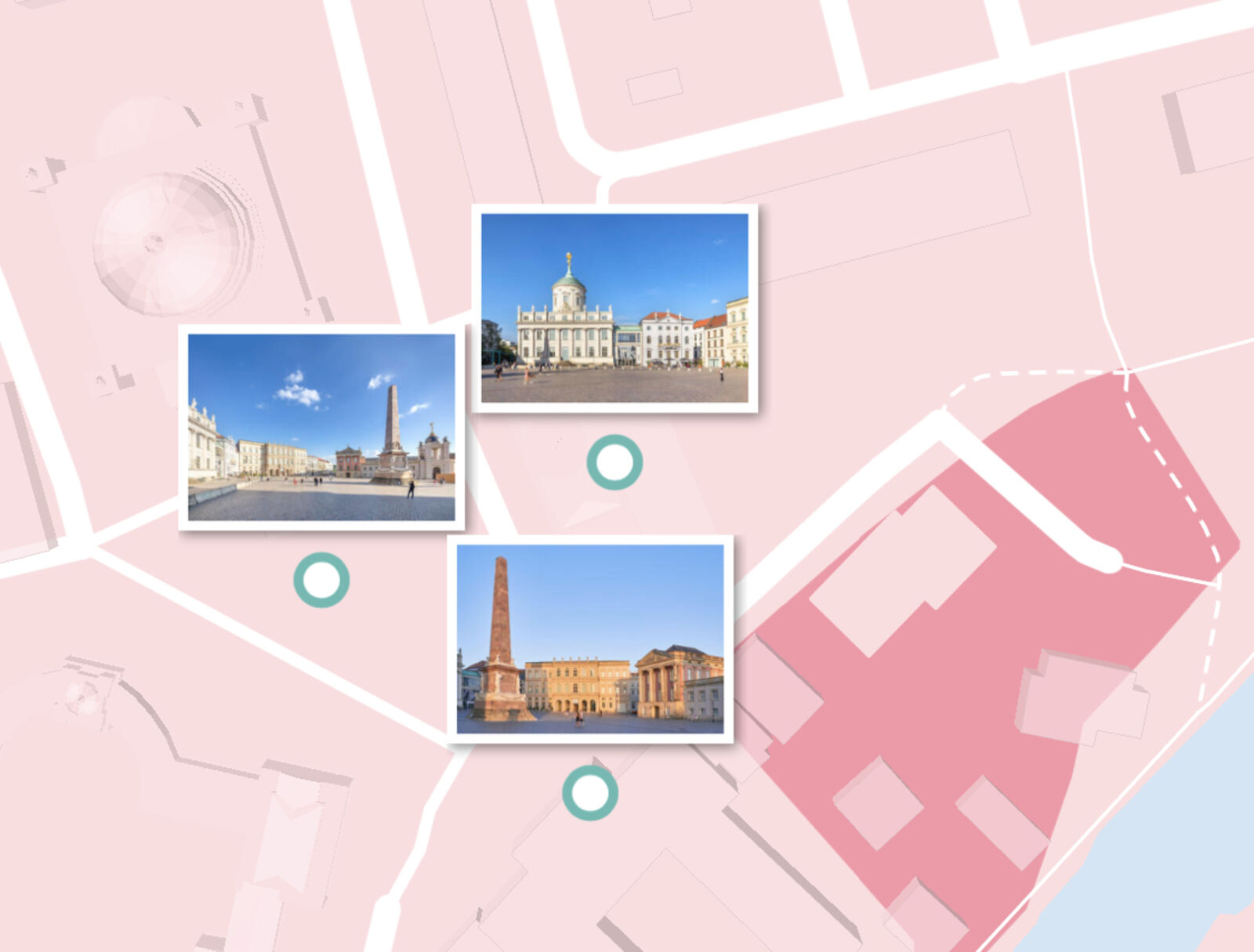

The Edict of Potsdam / Potsdam Museum

Who could have guessed that the origin of French culture and life here in Germany would be a piece of paper: the Edict of Potsdam, issued on October 29, 1685. In this decree, the Great Elector of Brandenburg addressed the citizens of France, who at that time were ruled by none other than the Sun King, Louis XIV. It was an astonishing act, in which the Elector of Brandenburg—ruler of what at that time was a relatively insignificant principality—stood up to one of the most powerful kings in Europe. As a result of the Edict of Potsdam, large numbers of French immigrants flowed into Brandenburg and the city of Potsdam.

David von Becker

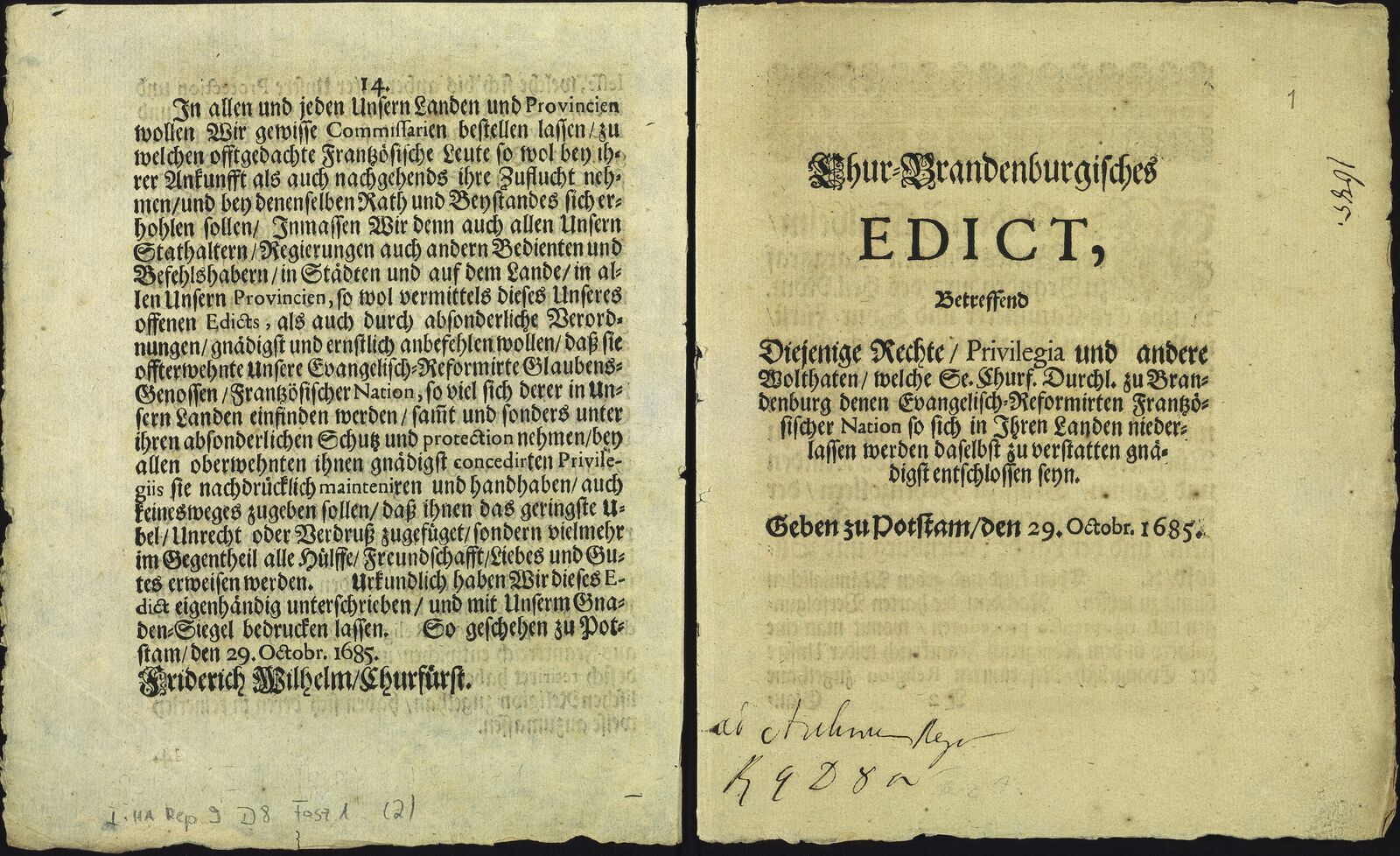

The Potsdam Edict of Toleration

Today, the edict is informally known as the Potsdam Edict of Toleration. It constituted the Elector’s response to Louis XIV’s revocation of the so-called Edict of Nantes. An entire section of the permanent exhibition in the Potsdam Museum is devoted to this edict.

So what happened?

The Edict of Nantes, promulgated in 1598, had guaranteed religious tolerance, civil rights, freedom of conscience, and the free exercise of religion to the Calvinist Protestants, or Huguenots, in Catholic France—with the exception of Paris and cities with a bishop’s seat or a royal palace. The revocation of this edict now meant that Protestantism was outlawed in France. Any Protestant who was not prepared to renounce his confession and convert to Catholicism had to leave the country.

The Edict of Potsdam was written in two languages, German and French. It offered Huguenot religious refugees the prospect of a new home in the electorate of Brandenburg and the duchy of Prussia, which also belonged to Brandenburg. To be sure, this invitation was also motivated by self-interest: in the wake of the Thirty Years’ War, Brandenburg had been depopulated, and its barren soil and swampy lands were in desperate need of laborers for reconstruction. The decree appealed to the refugees to rebuild “devastated and ruinous houses,” to make the land arable, and to establish workshops. The expectations placed on the French immigrants were very clear.

Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, GStA PK, I. HA GR, Rep. 9 Allgemeine Verwaltung, Nr. D 8 Fasz. 1

The Edict of Potsdam

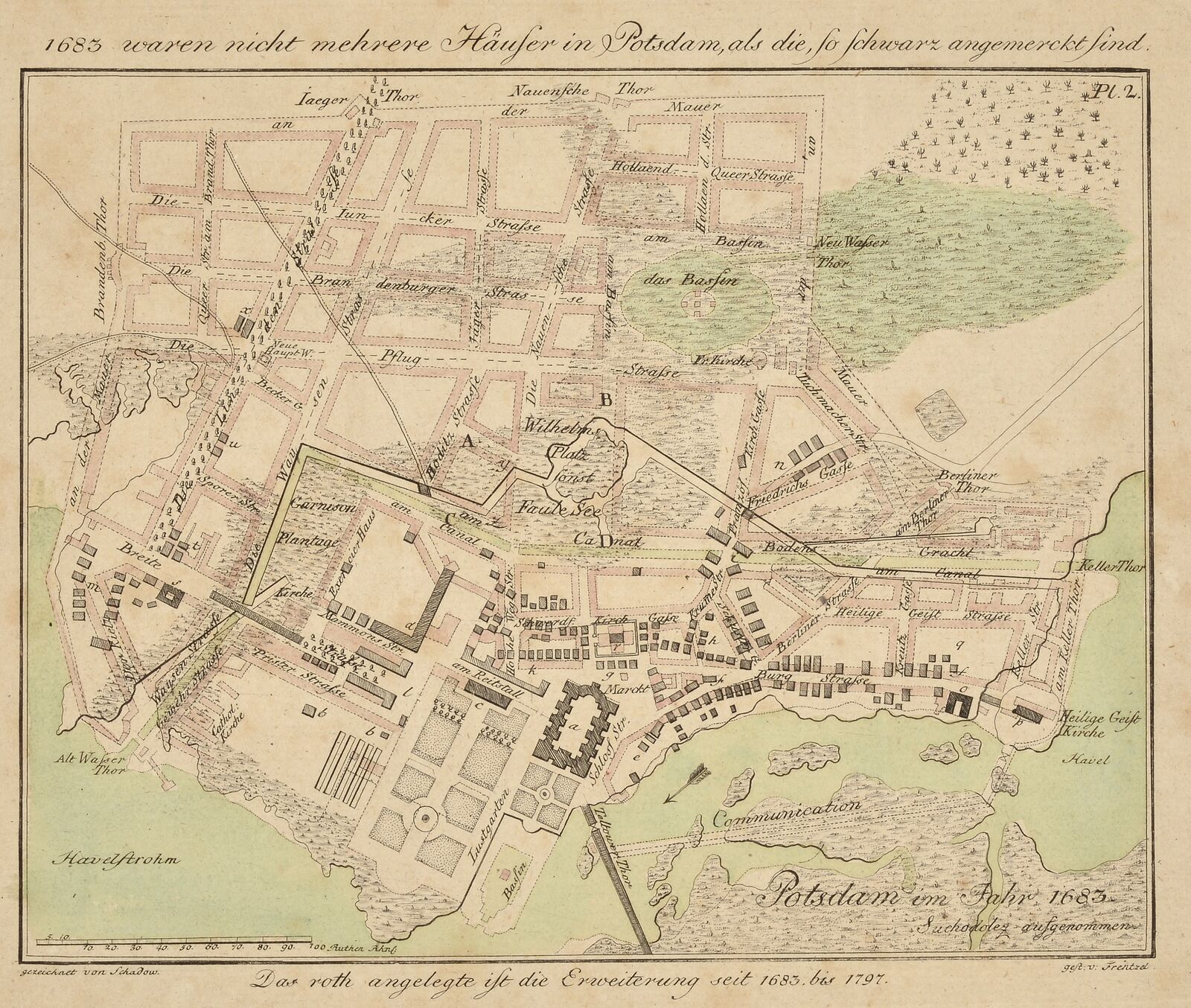

Engraving by J. C. Frentzel, photograph by Samuel von Suchodolez (1683), completed by Friedrich Gottlieb Schadow, Potsdam Museum – Forum für Kunst und Geschichte

City map of Potsdam with its extensions until 1797

First great refugee movement in Brandenburg

The Edict of Potsdam offered the immigrants generous conditions for settlement in war-ravaged Brandenburg. It guaranteed that their expenses would be covered as soon as they left France. They would receive material support, passports, financial assistance to cover the cost of travel to Brandenburg, the ability to choose where they wanted to live, and the freedom to worship in their mother tongue with a pastor who was paid by the elector. In addition, they were exempt from taxation for the first four years and were permitted to occupy vacant dwellings, or could receive assistance to build new ones. They were given the same rights as the native population, and could be naturalized without the demand for immediate integration.

The elector Frederick III, who came to power in 1688, continued to woo the Huguenots, and in 1701 he became king of Prussia as Frederick I. Since the elector had invited them, the new inhabitants were assured of the goodwill of the court, nobility, and most of the intellectuals. In the period around 1700, the social elites of Europe viewed the French language as the expression of a civilized lifestyle, and it was also spoken at the court in Potsdam. The Huguenots’ language served as proof of their cultural acceptability, and some of them even served as royal tutors at the court.

The immigration of the Huguenots is the first great refugee movement in Brandenburg’s modern history. Around 20,000 French citizens fled here to establish a new home. Beginning around 1720, more and more of the new arrivals settled in and around Potsdam, where the necessary housing had previously been lacking.

The process of resettlement, however, was not entirely without conflict. In those days, there were no official programs for integration, and mutual dislike, competition, and abuse were more the rule than the exception. At first, the ordinary people mostly rejected the French: they looked different, their language was foreign, and their Calvinist faith was strange to the Lutherans of Brandenburg. Their arrival also led to a shortage of housing and food, resulting in higher prices. Even more importantly, however, the local population saw their professional existence endangered and envied the newcomers their privileges. The guilds were reluctant to accept foreigners, and there were even incidences of arson and vandalism. Only gradually did the people begin to grow accustomed to each other.

The Potsdam Museum – Forum für Kunst and Geschichte is one of the stops on the audio tour France in Potsdam, which was developed for the Barberini App on the occasion of the French Impressionists moving into the Barberini Museum. The audio tour invites you to discover around 25 stops with French influences that have helped shape Potsdam over the centuries. Simply download the free Barberini App and be surprised by the city's many French references.